Tom Stoddart

A tribute to photojournalist Tom Stoddart who died on 17 November 2021.

In May 2022, at the three day Photo North festival in Manchester, hundreds of people gathered in an innocuous basement studio at the former Granada Studios in central Manchester to witness a photography exhibition, Extraordinary Women by Tom Stoddart. The following month, thousands made the pilgrimage 40 miles east through the great west doors of Chester Cathedral to view the same month-long show.

Some of the visitors were new to Tom’s photography, many more were loyal and had travelled great distances to see images by a man who had photography in his DNA. People journeyed to pay their respects and talk about the personal contact he had with them. Tom would regularly drive across the country to camera clubs and lecture theatres to deliver presentations. He wouldn’t talk about his awards, accolades, or the thousands of pounds he raised for charity, more motivated to share his enthusiasm for the profession that consumed his life, that and perhaps a bottle of wine.

After a gutsy fight against cancer, Tom passed away in November 2021, 11 days shy of his 68th birthday. His wife Ailsa said the house was quiet and full of light, just as he liked it and a lot like the man. After a life travelling the world and residing in London (including 20 years in Wapping) he had returned to his beloved north east of England. Tom left a legacy of half a century of photography covering many of the world’s major events and hotspots from the civil war in Lebanon, fall of the Berlin wall, Romanian Revolution and inauguration of South African President Nelson Mandela. These events contain some of the pictures he was proudest and tell the story with a thorough understanding and humanitarian quality.

Born in Morpeth, the son of a farm worker, young Tom’s morals were instilled by his mother and the headmaster at the mixed comprehensive school in the fishing village of Seahouses, where he rose to be head boy. From school, most of his peers said Auf Wiedersehen Pet and went off to build a life rebuilding Germany. Tom, however, spied an advertisement in the Berwick Advertiser for a photographer. Only having really achieved in English at school, a 17-year old Tom saw this as a platform to becoming a reporter and successfully applied – more down to having just passed his driving test than to possessing any photographic portfolio. After day two, and an assignment photographing on location at a Women’s Institute party, he knew photography was for him, rather than a life hammered out behind the typewriter. In 1978, he moved to London and began working as a freelancer for the Fleet Street tabloids and later, covering stories for the Sunday Times.

In the early 1990s, Tom photographed comprehensively in Bosnia & Herzegovina during the civil war tearing the former Yugoslavia apart. ‘After watching the TV pictures early on in the siege, I decided I had to go to Sarajevo to document what was happening. I arrived in the city in July 1991 and was immediately struck by how close it was to London, and other capitals in Europe,’ he said. His photographs from the siege of Sarajevo are amongst some of his most exemplary and show considerable bravery: women sprint across the most dangerous intersection of Sniper Alley where many Sarajevan’s were shot; five-year-old Amra runs into the arms of her mother Sedija who lost both legs after being hit by a grenade; a young widow grieves over the coffin of her husband in Sarajevo’s Lion cemetery; 67-year-old Antonia Arapovic hugs her neighbour’s child in the darkness of a cellar during a mortar bombardment; a young girl stares silently through a shattered window.

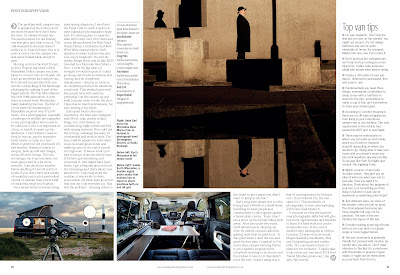

During the siege Tom was severely injured resulting in a shattered ankle and his shoulder fitted with a titanium plate. After taking a year out to recover, as soon as he was able, undeterred and with one leg now inches shorter than the other, he returned and captured one of his most praised photographs. ‘I was shooting a story about women in the siege and I saw this lady walking along towards me, it was in a part of the city called Dobrinja, which was a very difficult area to work in and I saw this kind of vision coming towards me and I just backed away from her and shot six, seven, eight frames maybe and then she was gone. When my agency distributed the set of photographs, LIFE magazine wanted to run this as a double page spread but of course I had no details, I didn't know who she was, her name or anything about her so I literally went back to Sarajevo with a photograph and asked around and found her. Her name is Meliha Varešanović. I was able to do an interview with her.’ The image of Meliha defying Bosnian Serb sniper bullets and mortar fire, wearing high heels, pearls and smart floral dress has become an iconic image of courage and dignity. His pictures from Bosnia were published around the world, highlighting the crisis and helped raise it to the top of the political agenda in European governments and embassies.

Tom’s commitment in what he believed was relentless. Rejecting advice that the HIV/AIDS pandemic wasn’t newsworthy or cost-effective, during the late 1990’s and early years of the new millennium, he travelled extensively, at his own cost, across Sub-Saharan Africa documenting the catastrophic AIDS crisis blighting the region. The resultant photo-essay, entitled Lest We Forget: AIDS In Africa, won first place in the 2003 Pictures Of The Year World Understanding Award. When Tom sent it to then Prime Minister Tony Blair (who gave Tom exclusive access to document his 1997 election campaign), he received a letter, part of which reads: I know from my own experience your dedication to your work and the power of your photographs. I’m delighted that your skills are being used to educate us all about what is, without any doubt, one of the biggest problems and challenges faced not by Africa but the whole international community.

Tom had begun transitioning from flash and long lenses to Leica cameras and fixed 28mm and 35mm lenses before landing in Yugoslavia. ‘I like to be as invisible as possible. My job is to creep in, capture moments that reflect what’s happening and then get out as quietly and quickly as possible. I like to build up a rapport with the people that I’m working with, the people I’m photographing in a difficult situation I find myself slowing down, you kind of drift in, you become completely non aggressive, your body language is very slow, the way you look at people, the way you talk, the way you speak, even the size of my cameras, the Leicas are very small cameras they have very silent shutters, everything is geared to building up a trust between myself and the people that I’m there to photograph.’ Tom is rarely pictured with a camera over his shoulder or with the lens cap on. They hang around his neck, one above the other, straps carefully tailored for maximum efficiency, always ready for the next shot.

A skilled craftsmen, Tom expected the same from those that worked with him as former assistant and now Tom’s image curator, Caroline Cortizo, testifies: ‘When I started to work for Tom, he sent me home with a really old Leica and lens that he didn’t use, I can’t remember what it was but it wasn’t one of his beloved M6s - this one was battered but still worked. Tom was so professional and with hindsight, protective, unless you could show him that you could load it in the dark, under pressure, you weren’t allowed to load the Leicas. He gave me the camera to go away and learn how to use it and to be able to change the film within a minute in the dark and I had to do that with a bag or a towel over my head, something to give complete darkness and also make you stressed and it worked. I would have to sit with him and show him I could do it. It did take a bit of time for him to trust me. The Contax and the Mamiyas, the SLRs were simple and he never doubted i’d not get these right but let me tell you when you are miles away from home in a god forsaken place like Sri Lanka after the Tsunami or in Chernobyl in a high stakes situation and where something was happening really quickly, Tom took full control. I can reflect and be proud of watching sweat drip of Tom’s nose in intense heat with stressed people all around us and the opportunity to unwind by hand his film and concentrate on loading correctly, consistently and focussed, it makes me think it helped him find his inner calm and concentrate on his job in hand. Those moments were at breathtaking speed but almost spiritual, dare I say it. He really didn’t want anyone to have that stress and far from thinking you weren’t good enough or he didn’t trust you what was going on was bigger than that. Tom always took full responsibility.’

Tom understood there was always more to learn. ‘A good photo editor can read what you’re thinking in the 36 frames on your contact sheets. They can teach you, they can show you your contact sheets and notice that you always seem to hit your best pictures at frame 16 or 17. They can show you you’re not bending your knees enough, that you’re shooting everything from the same height, simple things like that.’ For motivation, two photographs were fixtures in his office that he thought were among the greatest photographs ever taken: Larry Burrows’ 1966 colour photograph of wounded Marine Gunnery Sgt Jeremiah Purdie reaching towards a stricken comrade and Shell-shocked US Marine, The Battle of Hue 1968 by Sir Don McCullin.

An indicator of what kind of man Tom is and the impact that his photography has, is affirmed by those willing to collaborate. Actress, filmmaker, and humanitarian Angelina Jolie wrote the foreword to Extraordinary Women, Images of Courage, Endurance & Defiance (ACC Art Books 5 Oct. 2020). Singer-songwriter and political activist Sir Bob Geldof wrote the foreword to iWitness (Trolley Books 1 Oct. 2004) and former broadcast war reporter and independent politician Martin Bell the introduction to Edge of Madness, Sarajevo, a city and its people under siege (Hayward Gallery Publishing 1 May 1997). Looking to the future, devotees of Tom’s work will take comfort that with his blessing, work is already taking place for the legacy of his archive. Exhibitions in Germany, Bosnia and Newcastle are already being planned for 2023 along with a special evening at the Bosnian Embassy hosted by the Ambassador to honour Tom for all the work he did in Sarajevo.

I first met Tom in 2000 when I joined the prestigious Independent Photographers Group (IPG), part of Katz Picture Agency. IPG photographers were the big hitters, bull hippos and competition winners; they were the Katz cream and I lapped it up. For some beautiful and unfathomable reason, Tom took an interest in me and what I did. A professional interest became a personal friendship, mainly forged in the pub than on assignment. The photographers I admire the most are the ones who do what I don’t, I’d like to think that perhaps a small part of Tom felt the same.

As a source of inspiration to my family and I, Tom’s images hang around my home and his advice continues to reverberate around my head, some appropriated or parodies from other photographers but to me, indisputable ‘Stoddisms’: Photography is a champagne lifestyle on a beer salary; the most difficult thing is to keep swinging your legs out of bed; never trust a photographer with clean knees; If you photograph in colour, you see the colour of their clothes, but if you photograph in black and white, you see their soul; art photography is about look at me, photojournalism is about look at this; F8 and be there.

‘Photography doesn’t by itself change things that are wrong, it’s only one small part of something that may lead to change. When I’m on my own, you realise you’re a very small cog in all of this. There’s always the dream for any photographer, especially one whose covering news, you always dream of hitting the big moment. History is littered with photographs that are seen every day, the raising of the flag at Iwo Jima, the Kennedy assassination, the child running down the street in Vietnam. These are split seconds in history that every photographer would give his right arm to have taken and if I have a dream, it would be to leave behind one image that has become an icon for the period that it was taken in.’ The Leica Society Magazine was one of the last things Tom read and understood the importance of keeping this magazine going - the images across these pages suggest he has achieved well beyond his dream.

To keep up to date with developments of Tom’s legacy, exhibitions and publications visit: www.tomstoddart.com